Monopolies and Trusts: How and why did American business seek to eliminate competition?

Introduction

The industrial revolution in America not only transformed the production landscape but also sowed the seeds for some of the most significant economic entities: monopolies and trusts. As big businesses burgeoned, their ambitions swelled, driving many to eliminate competition and dominate their respective markets. This essay delves into this fascinating juncture in American history, exploring the rise of monopolies, the intricate workings of trusts, and the intricate dance between government regulations and business maneuvers. The ramifications of these monopolistic endeavors were not just economic but socio-political, creating waves that resonated throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

Historical Context and Emergence of Monopolies

The era following the Civil War, commonly termed the Gilded Age, marked a period of unprecedented economic growth and industrialization in America. Railroads expanded, factories mushroomed, and cities grew at an astonishing rate. Amidst this rapid development, individual entrepreneurs and corporations sought ways to maximize their profit, often leading to the suppression of competition.

One of the early manifestations of monopolistic tendencies was the formation of ‘pools’. Companies in the same industry would agree to fix prices or divide the market to reduce competition. However, these were temporary and easily broken. Soon, these transient arrangements gave way to more permanent structures in the form of trusts and monopolies.

A monopoly, in essence, is when a single company dominates an industry, either by owning all the means of production or by making it difficult for other companies to compete. Examples from the late 19th century abound. One of the most notable was John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, which at its height controlled over 90% of the oil refining in the U.S. Such dominion over a market allowed these entities not only to set prices but also to dictate terms of trade, often to the detriment of consumers and smaller competitors.

The lure of monopolies was unmistakable. With increased control came reduced risks, stable prices, and often, inflated profits. This consolidation wave was not confined to a particular sector; from steel to sugar, from oil to railroads, monopolies began to leave an indelible mark on the American business canvas.

Economic Rationale Behind Monopolies

At the heart of every business endeavor lies the pursuit of profit, and monopolies, in their essence, provided a robust framework for maximizing it. One of the driving forces behind the establishment of monopolies was the principle of economies of scale. Simply put, as a company expands its production, the average cost of producing each unit often decreases. This allows larger companies to produce goods more efficiently and at a lower cost than their smaller competitors.

With the reduction in costs, monopolies were in a unique position to either undercut competition or maximize profit margins, often leading to the former’s extinction. Furthermore, by controlling a large portion of the market share, monopolies had the unrivaled ability to set prices. This not only ensured a consistent revenue stream but also acted as a deterrent for potential entrants into the market.

Beyond pricing and cost advantages, monopolies also offered stability. In a competitive market, businesses often face fluctuations due to factors like price wars, unpredictable demand, or supply shocks. Monopolies, however, with their vast resources and control, could buffer against such instabilities. Their sheer size allowed them to manage supply chains, adjust production rates, or even influence market demand, ensuring a relatively predictable business environment.

Trusts: A Mechanism to Control Competition

While monopolies dominated industries through sheer size and control, trusts emerged as a sophisticated mechanism to govern multiple companies under a unified front. In essence, a trust was an arrangement where stockholders in several companies transferred their shares to a single set of trustees. In return, these stockholders would receive a trust certificate, essentially relinquishing their voting rights but still receiving dividends.

The trustees, now holding significant sway over the amalgamated companies, could coordinate policies and operations. This effectively eliminated competition among the entities under the trust while presenting a united front against external competitors. Standard Oil’s trust, for instance, was adept at this, leveraging its combined power to negotiate with railroads, secure discounts, and stifle competitors.

This era saw the rise of numerous trusts, from sugar to whiskey, tobacco to cotton oil. Their power was unparalleled, often drawing criticism from the public and politicians alike. These trusts not only controlled prices but also influenced production levels, wages, and even political decisions. In many ways, they epitomized the concentration of economic power, raising pertinent questions about their unchecked influence and the broader implications for American society.

Social and Political Implications

The rise of monopolies and trusts was not merely an economic phenomenon; it bore significant socio-political ramifications. To many Americans, these colossal entities represented the unchecked power of a few, leading to widespread public outcry and debates about the very fabric of American democracy and capitalism.

One of the most palpable implications was the wealth disparity. As trusts and monopolies amassed unprecedented wealth, a stark contrast emerged between the opulent lifestyles of the industrial barons and the often-dire conditions of the average worker. This disparity became emblematic of the Gilded Age, where the exterior glitter concealed deep-seated socio-economic issues.

Beyond the economic realm, monopolies and trusts exerted considerable influence on politics. With their deep pockets, they contributed generously to political campaigns, expecting—and often receiving—favorable policies in return. This blurred the lines between business interests and public governance, leading to widespread sentiments of distrust and disillusionment among the populace.

Socially, the rise of these entities fueled debates about the role of government in regulating business. Should the state intervene to curb the powers of these giants, or should the free market be allowed to self-regulate? This discourse would lay the groundwork for significant legislative changes in the years to come.

Government Response: Antitrust Movements

In response to the rising tide of public discontent and the evident socio-economic challenges posed by monopolies and trusts, the U.S. government began to take steps to regulate and curtail their power. The cornerstone of this effort was the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890.

The Sherman Act made it illegal to “restrain trade or commerce” and to “attempt to monopolize.” While its language was broad and somewhat ambiguous, it marked a clear intent by the government to rein in the unchecked power of big businesses. However, the act’s enforcement was initially tepid, with many early cases failing to secure convictions against the trusts.

The tide began to turn in the early 20th century, especially under the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt, often dubbed the “trust buster.” His administration launched a series of lawsuits against major trusts, with one of the most notable being the case against Northern Securities Company in 1904. This case signaled a more aggressive stance against monopolistic practices.

The subsequent years saw the introduction of more antitrust laws, such as the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914, which provided clearer definitions and guidelines to curb anti-competitive practices. These movements and regulations were instrumental in shaping the future of American business, ensuring a balance between free enterprise and necessary oversight.

The Long-Term Impact on American Business

The legal and societal backlash against monopolies and trusts indelibly impacted American business practices. Post the antitrust movements, businesses became more circumspect in their strategies, aiming for growth while being wary of potential antitrust violations.

While overt trusts dissipated, businesses found subtler means of collaboration and consolidation. Mergers and acquisitions became commonplace, often framed as means of efficiency and synergy rather than overt market control. This era also saw a rise in oligopolies, where a few firms would dominate an industry, subtly coordinating without the blatant appearance of a trust.

The legal framework around antitrust also evolved, with nuanced interpretations of what constituted ‘anti-competitive’ behavior. While the early 20th century was aggressive in trust-busting, later years saw a more lenient approach, focusing on consumer welfare and market efficiencies.

The legacy of this era persists today, with modern businesses continuously navigating the balance between market dominance and antitrust regulations. Recent debates around tech giants and their market control echo the dilemmas of the Gilded Age, showcasing the continued relevance of this historical chapter.

Counterarguments: Benefits of Monopolies

While monopolies and trusts often draw criticism for their anti-competitive nature, some argue in their favor, highlighting potential benefits. From an economic standpoint, monopolies, due to their scale, can lead to cost efficiencies, which could, in theory, result in lower prices for consumers.

Furthermore, monopolies might ensure stability in a market, preventing volatile price swings and ensuring consistent product or service availability. Some argue that monopolies, with their significant resources, can invest heavily in research and development, potentially leading to innovation.

These arguments, while presenting a nuanced view, often hinge on the behavior of the monopoly. A benevolent monopoly might indeed bring about efficiencies and innovations, but there’s no guarantee against potential exploitative practices in the absence of competition.

Conclusion

The tale of monopolies and trusts in American history is a vivid tapestry of ambition, economic maneuvering, and societal response. These entities, born out of the industrial fervor of the Gilded Age, reshaped the business landscape, prompting essential questions about market control, wealth distribution, and the role of government in overseeing commerce.

Today, as we grapple with the challenges and implications of market dominance by tech behemoths, the lessons from the past provide invaluable insights. The dance between free enterprise and regulation is intricate and ongoing, with history serving as both a guide and a cautionary tale.

Class Notes – How and why did American business seek to eliminate competition.

As business expanded natural predatory instincts took over as companies sought to eliminate competition. It was survival of the fittest in an economy which did not regulate business – laissez

faire, social Darwinism, rugged individualism where the themes of the day.

Clearly the natural conclusion of laissez faire capitalism, or pure competition, is the end of competition itself. It is the natural goal of any business to make as much profit as it can and to

eliminate its competition. When a corporation eliminates its competition it becomes what is known as a “monopoly.”

Monopolies took several organization forms including what were known as trusts.

Trust

Stockholders of several competing corporations turn in their stock to trustees in exchange for a trust certificate entitling them to a dividend. Trustees ran the companies as if they were one.

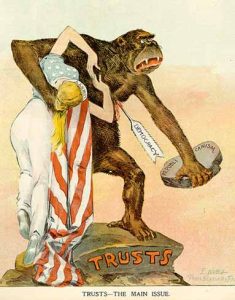

This political cartoon published The Verdict on July 10, 1899 by C. Gordon Moffat shows an America controlled by the trusts.

To the public all monopolies were known simply as “trusts.” These trusts has an enormous impact on the American economy. They became huge economic and political forces. They were able to manipulate price and quality without regard for the laws of supply and demand. Basic economic principles no longer applied They also had great political power. Trusts were extremely influential in Congress and in the Senate. Some even accused the trusts of “buying” votes. Although many Americans still regarded men like John D. Rockefeller as “Captains of Industry,” more and more people began to publicly question the tactics of the “Robber Barons.” As trusts grew ever more

powerful and wealth became concentrated in fewer and fewer hands, animosity towards the new businessmen and the new methods of doing business increased tremendously.