Farmers’ Responses to Industrial Revolution Challenges

Introduction

The Industrial Revolution, spanning the late 18th to early 20th centuries, marked a seismic shift in economic and social structures worldwide. The United States, while benefiting from numerous technological and infrastructural advancements, also bore witness to a plethora of challenges, particularly for its agrarian communities. The rise of factories, railroads, and urban centers often overshadowed the profound struggles that American farmers faced. But in the shadow of industrial giants, the resilience and adaptability of farmers became evident. They grappled with changing markets, fluctuating crop prices, and mounting debts, leading them to seek various avenues to navigate these challenges.

This essay delves into the myriad strategies farmers employed during the Industrial Revolution. Through economic adaptability, political mobilization, and technological innovation, these agrarian pioneers sought to redefine their place in an evolving nation.

Economic Challenges and Responses

Declining crop prices

One of the major challenges farmers faced during the Industrial Revolution was the steady decline in crop prices. As industrialization increased the efficiency of production and transportation, farmers could produce more crops, leading to an oversaturated market. Additionally, foreign competition further exacerbated this saturation, with international goods frequently entering the domestic market.

In response to these dwindling prices, many farmers sought to diversify their crops. By expanding their agricultural portfolio, they could tap into niche markets and reduce their dependency on a single crop’s market performance. Collective bargaining also emerged as a popular strategy. Farmers began to organize and negotiate collectively, striving for better prices and terms for their produce.

Increasing debt

While the Industrial Revolution brought forth a host of advanced farming equipment, such machinery often came with a steep price tag. To acquire these tools and capitalize on their benefits, many farmers took on significant debts. This financial burden, combined with declining crop prices, led to a precarious economic position for numerous farmers. The reliance on credit, often at exorbitant interest rates, further fueled their indebtedness.

In light of these mounting debts, farmers began to establish cooperatives and credit unions. These institutions aimed to offer loans at fairer rates and fostered a sense of community and shared responsibility among members. By pooling resources and knowledge, farmers sought to break free from the shackles of debt and assert greater control over their economic destiny.

Sociopolitical Responses

Populist Movement

Perhaps the most vivid sociopolitical response to the plight of farmers was the rise of the Populist Movement. Originating in the late 19th century, this grassroots movement was born out of widespread agrarian discontent. Farmers felt marginalized by the dominant economic and political forces, and the Populists sought to amplify their voices on the national stage.

The Omaha Platform, adopted by the Populist Party in 1892, encapsulated the hopes and demands of American farmers. Advocating for a more flexible monetary system, direct election of senators, and various reforms to counteract the monopolistic tendencies of big businesses, the platform sought to level the playing field for farmers. While the Populist Party itself struggled to gain a foothold in mainstream politics, its ideals and principles permeated American political discourse and set the stage for subsequent reform movements.

Granger Movement

Before the rise of the Populist Movement, the Granger Movement, or the Order of the Patrons of Husbandry, had already sowed the seeds of agrarian protest. Established in 1867, the Grange aimed to address the widespread isolation felt by many farmers. Through social, educational, and cooperative initiatives, the Grange fostered a sense of community among its members.

More than just a social club, the Grange became a potent political force, particularly in the Midwest. The movement lobbied for legislative reforms to curtail the power of railroads and big businesses, which were seen as exploiting farmers with high freight rates and monopolistic practices. This activism culminated in the Granger Laws – a series of state statutes that sought to regulate railroad rates and grain storage fees. Though many of these laws were later declared unconstitutional, they highlighted the growing political clout of farmers and their determination to challenge the status quo.

Farmer Alliances

In tandem with the Granger and Populist movements, various regional farmer alliances sprouted across the country. From the Southern Farmers’ Alliance to the Colored Farmers’ National Alliance and Cooperative Union, these groups united farmers under a common banner, advocating for economic and political reforms.

The alliances played a pivotal role in bridging the divide between rural and urban populations, bringing to the fore the issues faced by the agrarian community. Through lectures, publications, and rallies, they spread awareness about unfair lending practices, the need for better transportation rates, and the importance of cooperative buying and selling. These alliances, while region-specific in their origin, underscored the universal challenges faced by farmers and the collective spirit with which they sought to overcome them.

Technological and Innovative Solutions

Adoption of new farming techniques and tools

The Industrial Revolution wasn’t solely an urban phenomenon; it also brought transformative changes to agricultural practices. The introduction of new farming techniques and tools reshaped the American agricultural landscape. The mechanization of farming, with inventions such as the reaper and later the tractor, allowed farmers to increase their efficiency, producing more with less manual labor.

However, simply owning advanced tools wasn’t enough. Farmers needed knowledge about their optimal use and maintenance. This led to a surge in interest in scientific farming practices. Concepts like crop rotation, soil conservation, and advanced irrigation techniques started gaining traction. By embracing science and technology, farmers aimed to optimize their yields and ensure the sustainability of their lands for future generations.

Transportation solutions

Transportation was both a boon and a bane for farmers during the Industrial Revolution. While railroads enabled farmers to reach distant markets and expand their consumer base, they also often faced exploitative rates and services from the railroad companies. This dichotomy compelled farmers to seek better transportation solutions.

Many began to rally for more equitable railroad rates and better services, leading to legislative efforts to regulate the industry. Additionally, farm journals, a popular medium of communication during this era, played a pivotal role in disseminating information. These journals shared tips on efficient crop storage for transportation, advocated for fair railroad practices, and kept farmers updated on the latest technological innovations.

Collective Organizing and Co-operatives

The importance of farmer co-operatives

One of the most impactful strategies farmers employed to address their challenges was the establishment of co-operatives. Beyond mere economic entities, these co-operatives represented a collective voice and a united front against larger industrial and commercial powers. By banding together, farmers aimed to pool their resources and reduce their dependency on middlemen.

Co-operatives functioned on a simple yet powerful principle: strength in numbers. Farmers, through these entities, could directly negotiate better prices for their produce, obtain essential supplies at reduced costs, and share the risks associated with farming. Furthermore, co-operatives provided a platform for farmers to exchange knowledge, best practices, and innovative farming techniques.

Cooperative extension services

The idea of knowledge-sharing among farmers gained further momentum with the establishment of cooperative extension services. These services, often linked with agricultural colleges, played a vital role in bridging the gap between academic research and real-world farming practices. Extension agents would travel to various farming communities, conducting workshops, demonstrations, and lectures on the latest advancements in agriculture.

Through these services, farmers were introduced to novel farming techniques, pest control measures, and crop management practices. The Hatch Act of 1887 played a crucial role in this, providing federal funding to agricultural experiment stations in every state. These stations, in conjunction with extension services, ensured that American farmers remained at the forefront of global agricultural innovation.

Policy and Legislation

The push for favorable policies

As farmers grappled with the rapidly changing economic landscape of the Industrial Revolution, they realized the importance of favorable policies to safeguard their interests. With mounting concerns over exploitative railroad practices, monopolistic tendencies of big businesses, and unfair loan systems, the agrarian community sought legislative solutions.

Railroad regulations became a focal point of their advocacy. Farmers lobbied for transparent and equitable pricing, pushing back against discriminatory rates that favored big industries at their expense. Additionally, the fight against monopolies and trusts, which dominated various sectors and suppressed competition, became a central theme in their quest for fairer policies.

Key legislation

Several pieces of legislation during this period highlighted the farmers’ struggles and their efforts to bring about meaningful change. The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 was one such landmark legislation. Aimed at curbing monopolistic practices, the act sought to promote fair competition and prevent commercial entities from unfairly dominating markets.

Furthermore, the Hatch Act of 1887, previously mentioned in the context of cooperative extension services, showcased the federal government’s commitment to agricultural innovation and research. By funding agricultural experiment stations in every state, the act sought to place American agriculture at the pinnacle of global advancements.

While not all legislative efforts bore immediate fruit, they collectively represented the growing influence of the agrarian community in national policymaking. These laws laid the groundwork for subsequent reforms, ensuring that the farmers’ voices, often marginalized in the grand narrative of the Industrial Revolution, were heard and acted upon.

Conclusion

The Industrial Revolution, often lauded for its urban achievements and technological marvels, also bore witness to the tenacity and adaptability of American farmers. Faced with a deluge of challenges, from declining crop prices to the might of monopolistic industries, the agrarian community showcased remarkable resilience. Through economic innovation, sociopolitical mobilization, technological adoption, and the sheer power of collective organizing, farmers sought to carve out their space in a rapidly changing nation.

The multifaceted strategies employed by these farmers were not mere reactions to adversity but a testament to their visionary approach. They recognized the potential of collective bargaining, the value of shared knowledge, and the importance of favorable policies long before these concepts became mainstream. The cooperative spirit, the relentless quest for innovation, and the drive for equitable policies laid down by the farmers during the Industrial Revolution continue to inspire modern movements and reforms.

In the broader tapestry of American history, the farmers’ endeavors during this period serve as a poignant reminder of the nation’s foundational values: hard work, community, and the undying spirit of progress. As we reflect on the transformative era of the Industrial Revolution, it’s essential to acknowledge and celebrate the farmers’ invaluable contributions, for they truly were the unsung architects of America’s industrial age.

Class Discussion and Notes

While we have studied the trails and triumphs of industrial revolution we would be negligent if we only focused on industry. Workers need to be fed and the plight of farmers was and always will be of critical importance. While cities may represent the wealth of America, it is the farms and the Midwest that are the breadbasket and heartland of this nation. This poem, written by a farmer at the turn of the century reminds us of this.

When the banker says he’s brokeAnd the merchants up in smoke,

They forget that it’s farmer who feeds them all.

It would put them to the test

If the farmer took a rest;

Then they’d know that it’s the farmer feeds them all.

Farm Prices Drop

The post Civil War era represented both triumph and tragedy for the farmer. The population boom caused by the end of the war increased demand and farmers met the demand. The increased business was a welcome sight for farmers. The industrial age made farmers more efficient as well. Just as the steel plow and the cotton gin had increased productivity, so did irrigation and the tractor. Farm production skyrocketed. As with any product the greater the

supply, the lower the price. In response to this deflation farmers

did what they knew how do do, grew more crops! Generations of farmers were always taught that the way to make more money was to grow more. This time however as production continued to increase, prices continued to fall. Farmers actually MADE LESS! The consequences were devastating.

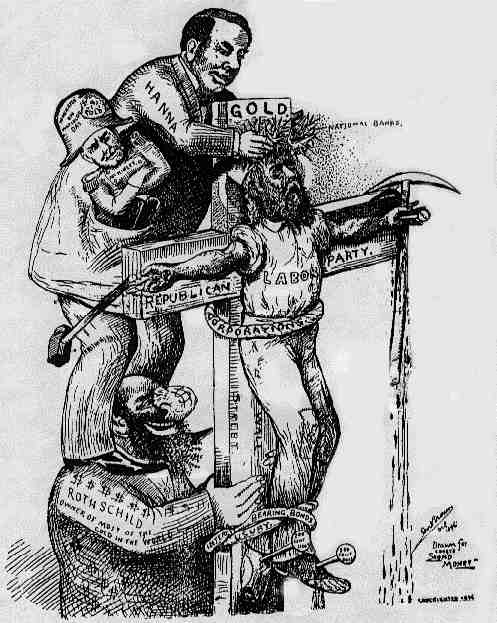

The Gold Standard Makes Deflation Worse

In 1900 America went on the Gold Standard. What this meant was that every dollar was exchangeable for a dollar of gold. The US promised to have gold reserves equal to the amount of money in circulation. The problem with this is that is limits the amount of money in circulation and this raises the value of money. The effect of this on farmers was further deflation. Their loans on farm acreage remained but their income dropped…not a good combination.

Farmers Form The Populist Party

In response to their problems farmers formed a political party called the Populist Party. The elected William Jennings Bryan as their leader and first candidate for president. As a third party the Populists hoped to get their ideas and needs placed into the public arena. Perhaps they realized that a Populist would never be elected president but they had a good chance that one of the major parties would incorporate the populist message into their platform. The Populist sought the following:

- Elimination of the gold standard. Populists supported the Silver Standards which would have made money cheaper and more available. This would have created inflationary pressure and raised prices. If a silver standard would not be accepted they would have settled for bimetallism.

- Passage of an income tax.

- The end of life tenure of Federal Judges.

- The end of the printing of paper currency by nationally chartered private banks.

The Populist Party did not achieve all of their goals, the nation remained on the gold standard until 1933, but they did get considerable recognition as a viable political force. By 1911 the new Federal Reserve System took over the printing of money. An income tax was indeed passed. Perhaps most importantly they proved that a third party could influence national politics and generate legislation.

The American Novelist Frank Baum wrote an interesting story about the plight of the farmer. Perhaps you have heard of it? It is called The Wizard of Oz. Surprised? Dorothy represents every woman, the good of the mid west. Where is she from…Kansas. She is transported to Oz where she lands on the Wicked Witch of the East.

The East and West witches represent the East and West coasts. Old money and power. The good witches are North and South, less powerful, they lie in the center of than nation, the agricultural areas. Dorothy must travel to Oz, where the all powerful Wizard lives in the Emerald City. Emerald is green, the color of money. This represents Washington DC where money rules. To get to the city she must travel on the yellow brick road. Yellow…gold! Gold will get her Washington. Along the way she meets several characters. The Tin Man.

He represents the industrial worker whose heart has been torn out by the evils of factory work and industrialism. The Scare Crow. This is how the farm worker is seen, without a brain. The Cowardly Lion. He represents William Jennings Bryan. If you ever saw the movie Inherit The Wind you would understand. Bryan had this loud booming voice, like a lion. Bryan also failed to get many of his reforms accomplished. When Dorothy finally gets to Oz (Washington DC) she meets the all powerful wizard who is supposed to be able to send her home to Kansas. Instead she finds him to be weak and flawed, in fact he is a charlatan who can only deceive himself and others. Guess who he represents…the President!! In the end how does Dorothy get

home? She is given ruby slippers, but in the book they are silver! The silver standard, if you remember is what the Populist Party wanted to end farm problems with deflation. The reality, however is that it turns out she had the power all along within herself. A final message that the farmers had it in themselves to solve their own problems. There is more but space limits the discussion.